The premier inshore sport fishing target in Texas is a prehistoric monster.

It’s not fit to bring home for supper. It’s ornery and downright stubborn for anglers. And, most of all, it’s simply hard to locate.

Meet Megalops atlanticus, the “silver king.”

Big tarpon are distinctive to say the least. Cloaked in shimmering chrome scales larger than the size of your fist and equipped with a protruding, upturned jaw, these fish are a sight to behold. That’s certainly on full display when a determined angler hooks one and the behemoth erupts completely out of the water, signaling that something primordial is on the other end of the line.

Despite its looming stature, the tarpon remains somewhat of a mystery to biologists and anglers alike. Silver king habitat includes a massive range of water spanning the entire Gulf of Mexico and up the eastern seaboard. However, despite this widespread prevalence, the overall tarpon population continues to face a number of challenges. These include both naturally occurring and manmade obstacles that have put a renewed spotlight on the conservation of the species and other saltwater dwellers alike.

Texas tarpon fishing history

Do you know where Tarpon, Texas, was located?

If you pinpointed present-day Port Aransas on a map, you’d be mostly correct. At one time, this part of the coast was dubbed the “Tarpon Capital of the World” and anglers and dignitaries from around the world flocked to the town of Tarpon to pursue prolific numbers of “silver kings” found cruising the nearshore Gulf of Mexico waters.

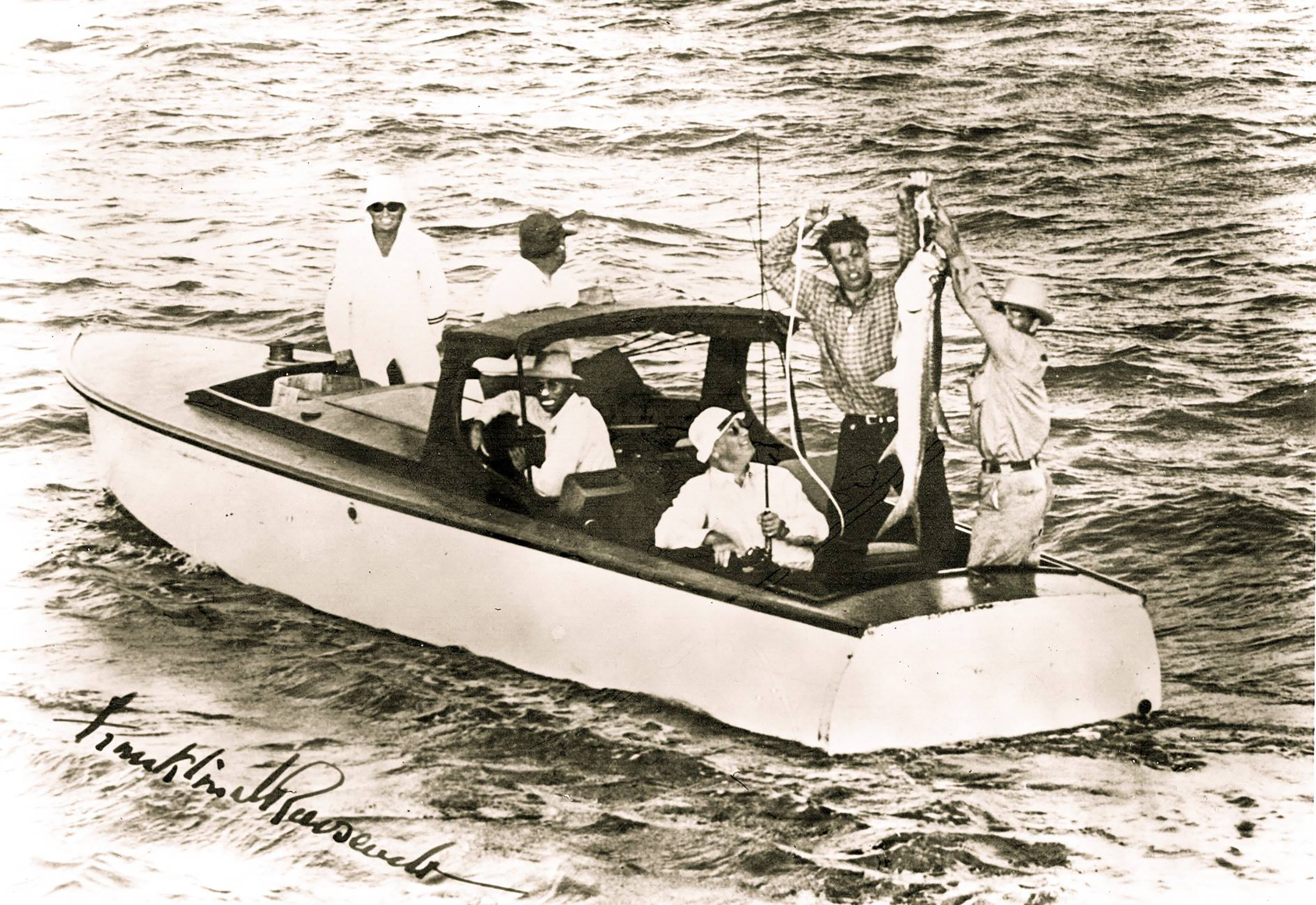

Among them was President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who in May 1937 caught a 5-foot tarpon weighing 77 pounds. A scale from that fish – along with thousands of others – has adorned the walls of the famed Tarpon Inn in Port Aransas ever since. Most were inscribed with the date and size of the tarpon caught, highlighting just how common tarpon were on the Texas coast through the early 1900s. Upon closer inspection, one will see that most of the scales on the walls were dated before the World War II years, emphasizing another dilemma: What happened to Texas tarpon?

That question has lingered for decades among anglers, biologists and conservationists. Among them was noted Port Aransas historian John Guthrie Ford. Before he passed away in 2018, Ford produced many notable works for the Port Aransas Historical and Preservation Association, including oral histories and books, as well as transcribing the Mercer logs (handwritten journals kept by the Mercer family who lived in the area in the 1800s).

His research suggests the tarpon fishing industry in the area began with the construction of the Aransas Pass jetties in the late 1800s and was aided by the formation of the Tarpon Club, a group of notable and wealthy anglers. That group would help usher in the pursuit of tarpon from the famed Farley boats, named for the family who helped develop the crafts for recreational fishing.

In the tarpon fishing heyday, scores of huge fish were killed and brought to the docks up and down the Texas coast, documented in countless photographs, some of which can be seen at the museum in Port Aransas. Then, after World War II and with more human expansion, the tarpon that had been so common in previous decades simply stopped showing up.

Researching Texas tarpon

Larry McKinney knows all about Texas tarpon.

He spent more than two decades with Texas Parks and Wildlife and was coastal fisheries director before assuming the role of executive director of the Harte Research Institute in Corpus Christi. McKinney, currently HRI Chair for Gulf Strategies, said the overall Texas tarpon story is one of many twists and turns.

“I’ve obviously been interested in tarpon along the coast and have been following the history of them going back to when we first started seeing declines after the droughts of the 1950s,” McKinney said. “At that time, we didn’t have many reservoirs built or dams on major rivers, and one of the things I did years ago was to track the development of dams throughout the state of Texas starting then up through the 1990s.

“Of course, now we know those manmade changes cut off a lot of freshwater that was going into our bays and estuaries, and that had a big impact on tarpon because they need that freshwater coming in. When they didn’t get it, that’s when we started seeing the tarpon numbers disappear to a great extent.”

McKinney points out that tarpon research has shown there are two separate populations of migrating fish, one from Florida and one from Mexico, with the Mississippi River Delta dividing their east and west movements. He said the Delta area featuring estuaries and freshwater inflows represents one of the main feeding grounds for the fish.

While those populations represent the majority of tarpon along the Gulf Coast, McKinney said tarpon have continued to show up in other areas where they likely shouldn’t be, which could mean the overall population is actually rebounding.

“One thing we saw back in the freeze of 2021 (Winter Storm Uri in February) were tarpon that were impacted and were found floating in the Upper Laguna Madre,” McKinney said. “Research teams went out and actually found small tarpon in back bay areas along the coast, some up to 4 feet long. And then people always seem to catch smaller tarpon from time to time at the jetties up and down the coast, sometimes when the larger migrations aren’t occurring.”

McKinney noted another issue facing tarpon due their migrating nature is they often are caught in nets in Mexico, where they are sold as a cheap option to eat. McKinney said the same thing occurs in Cuba, a locale he visited as part of a team attempting to help develop the recreational tarpon fishery there and help conserve tarpon that frequented the waters near the island nation. He said those efforts unfortunately didn’t come to fruition, and like Mexico, Cuba continues to see tarpon that end up in nets.

Looking toward future tarpon conservation efforts, McKinney is quick to point to one great source of information: the late outdoor writer Hart Stilwell, whose nearly finished manuscript was edited into a book titled “Glory of the Silver King.” It captures the history of tarpon and snook fishing on the Texas coast from the 1930s to the end of Stilwell’s life in the early 1970s. McKinney provided the foreword for the book.

“When I was at Parks and Wildlife, one of the writers on the magazine came to me with a box sent to them by the Stilwell family,” he said. “I read the manuscript and I said ‘we have to get this published.’ Brandon Shuler did a great job of editing all the work together and it helped to highlight the importance of what was an outstanding fishery and the need to help conserve our natural resources.”

One key element that has come about due in large part to an increasing focus on tarpon conservation is acoustic tagging. The Bonefish & Tarpon Trust began the Tarpon Acoustic Tagging Project in waters off Florida during the past decade and the program has grown to include a collaborative effort from Chesapeake Bay all the way across the Gulf of Mexico. That effort includes “Tarpon Alley,” a known hot spot on the upper Texas coast, and the waters off South Padre Island, another key tarpon migration route.

Acoustic tags inserted into a tarpon’s abdomen provide the ability to track them for up to five years. They are also small enough they can be used on juvenile tarpon as small as 5 pounds and larger fish exceeding 200 pounds. When a tagged fish swims within range of an underwater receiver – of which there are more than 4,000 through the now multi-state collaboration – the receiver detects and stores the tag’s unique code. That data has provided researchers with boatloads of insight into tarpon migration and habitat preferences.

South Texas tarpon fishing paradise

Brian Barrera caught the tarpon fishing bug years ago and he’s hooked on silver kings. The fishing guide enjoys putting clients on snook, redfish, speckled trout and flounder in the Lower Laguna Madre for much of the year, but his real passion is pursuing tarpon, especially the big ones.

Barrera has guided for tarpon in the South Padre Island area for more than a decade and in that time has built up a huge inventory of silver king knowledge. That being said, he’s also quick to point out that he still seems to learn something new on almost every trip up and down the shimmering Gulf beaches.

“We have a shorter tarpon fishing window here in Texas than other hot spots like Florida so you have to make the most of your opportunities,” Barrera said. “Mostly that revolves around the weather and the conditions on the water that might limit how often you can get out there. I’ve been fishing for tarpon for more than 10 years and I’m really still new to it even though I’ve helped people land a lot of fish. I do enjoy that learning aspect of it.”

Barrera said that as with other known tarpon haunts farther up the Texas coast, there are likely more resident tarpon than many realize. The jetties seem to always harbor smaller fish, even some weighing less than 10 pounds, he said. In terms of an annual window of tarpon time, the movement of fish depends largely on the weather and water conditions.

“The tarpon will start migrating up here typically in May once the water temperature starts to stay in the 70s and my tarpon season runs through October,” Barrera said. “The first migrating fish that show up are usually smaller – anywhere from about 25 to 80 pounds or so – and in each successive month the larger fish will come in. Later in the season is when we start seeing fish well above 100 pounds and even larger.”

Tarpon are either smart, or simply stubborn, when talking about lures they’ll take. Barrera employs a number of methods including live and dead bait, typically menhaden or mullet, and artificial offerings such as the D.O.A. Lures Bait Buster or the “Coon Pop,” named for Louisiana tarpon legend Coon Schouest, a type of jig head/soft plastic to which a large circle hook is wired. Trolling each of those along the beach is the typical fish-finding method when not attempting to track down rolling tarpon by sight fishing.

The proof is in the pudding for Barrera. Texas law allows an angler to retain only one tarpon per day and imposes a minimum length requirement of 85 inches – a framework designed to prevent harvest of any tarpon that doesn’t have a chance of setting a state record.

The current record Texas tarpon is a 90-inch fish weighing 229 pounds that was caught on the upper coast in August 2017. Barrera said he has seen tarpon firsthand that could have certainly challenged a fish of that size.

“Last year was the best tarpon season I’ve had. We put more than 200 tarpon in the air for clients and landed almost 100,” Barrera said. “That included lots of fish in the 140- to 160-pound range and a few more in the 180- to 200-pound range. All of those fish were released and not a single fish was killed.”

Crabbing along Texas coast geared toward simplicity, fun, food

Texas jetty fishing provides some of the finest angling conditions imaginable

Texas angler recounts painful encounter after stepping on stingray